Why do we feel shame about loneliness?

It’s an almost universal experience, and yet it is still a taboo. Olivia Laing discusses her own encounter with loneliness, and explains why overcoming any shame in this very human struggle is the first step to a happier life

The first time I really encountered serious intractable loneliness, I was in my mid-thirties. A relationship had started and ended in quick succession. The man in question lived in New York and, while we were together, we had planned that I’d leave Britain and join him permanently in the States.

Instead, I went alone, living in a run of cheap, tiny sublets. I did have friends, but none of the normal routines that constitute a life (always a peril for the freelance writer), so it was not surprising that I began to experience paralysing loneliness.

Break-ups and moves are exactly the sort of things that can trigger a spell of loneliness – a painful and distressing feeling that most of us have experienced at one time or another. Loneliness is the result of not having as much love and closeness as we would like, and although it is often thought to afflict those who are solitary, it can also strike people in relationships or who have busy social lives. Simply living alone does not mean you will feel lonely, while even marriage does not offer absolute protection against feelings of isolation or a longing for more intimacy.

Feeling invisible

One of the most frightening things about loneliness is the way it feels like it drives others away. I remember sitting as a teenager outside a train station in Worthing, waiting for my father. It was a sunny day, and I had a book I was enjoying. After a while, an elderly man sat down next to me and tried repeatedly to strike up conversation. I didn’t want to talk

to him and, after a brief exchange of pleasantries, I began to respond more tersely until eventually, still smiling, he got up and wandered away. I’ve never stopped feeling ashamed about my unkindness, and nor have I ever forgotten how it felt to have the forcefield of his loneliness pressing on me: an overwhelming need for attention and affection, to

be heard and touched and seen.

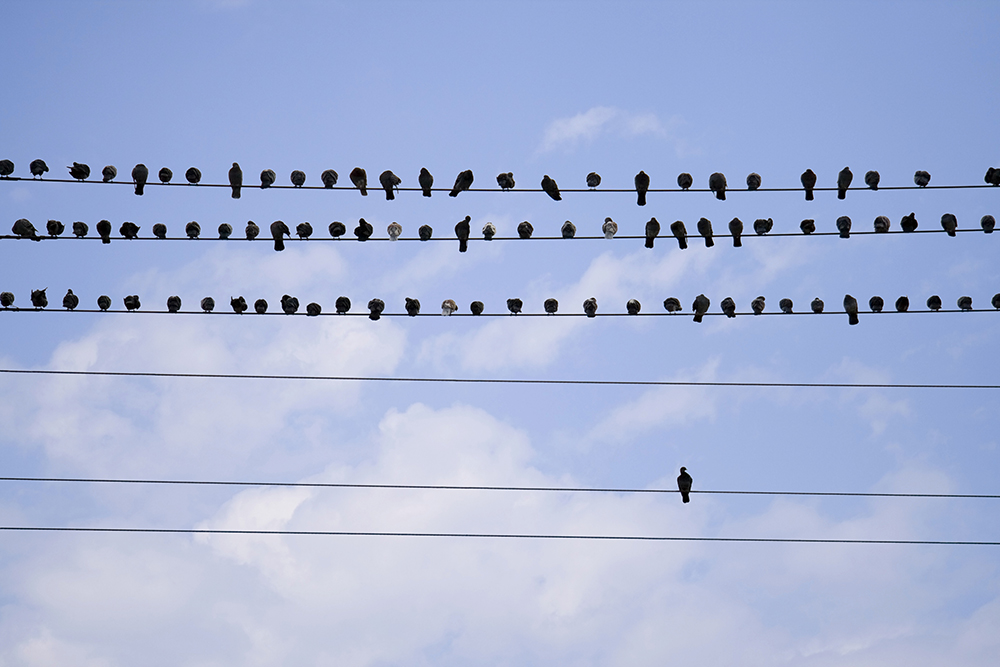

If it’s difficult to respond to people in this state, it’s harder still to reach out from it. Loneliness feels like such a shameful experience – so very counter to the sociable, populated lives we’re all supposed to lead – that it becomes increasingly inadmissible, a taboo state that will cause others to turn and flee.

What did loneliness feel like for me? It felt bad. It felt like being invisible, about a million miles from anyone else. At the same time I felt painfully exposed, sticking out like a sore thumb in a world made up of families and couples. As the months went by, I grew more hesitant about speaking to other people, and became increasingly withdrawn. I didn’t want to tell my friends, for fear they would back away in horror and, as a result, I kept myself to myself, getting lonelier by the day.

Later, I found out that this was a textbook presentation. It turns out loneliness really does get worse as it goes on. According to psychologists working on the subject, loneliness damages an individual’s ability to understand social interactions, initiating a devastating chain reaction, the consequence of which is to create growing alienation.

It works like this. When people enter into an experience of loneliness, they trigger what psychologists call hypervigilance for social threat. In this state, which is entered into unknowingly, the individual tends to experience the world in increasingly negative terms, and to both expect and remember instances of rejection – an unfriendly encounter in a shop, say, or a dismissive tone used by a friend that in different circumstances might not register.

Over time, these experiences are given greater weight and prominence than other more benign or friendly interactions. This creates a vicious circle, in which the lonely person becomes increasingly more isolated, suspicious and withdrawn. Worst of all, because the hypervigilance hasn’t been consciously perceived, it’s by no means easy to recognise, let alone correct, the bias.

Making sense

Learning this helped me to make sense of how I was feeling. I began to see why small negative interactions in cafés or shops were making me feel so unsettled, and to understand why I was becoming increasingly withdrawn. Knowing loneliness was distorting my perception meant that I could work consciously to correct the bias – to keep telling myself that I was slipping into paranoia, to retain my positivity and hopefulness. This understanding was powerful. It meant I could do something about it.

Slowly, it was dawning on me that I wasn’t the only lonely person in the world. There were others out there; millions of them, all lonely for different reasons. Some had suffered bereavement, some were shy, some lacked social skills and others, like me, had become unmoored after a change in circumstance.

One of the saddest things I discovered is that deep, lifelong loneliness can stem from childhood experiences of neglect and abuse. Recent research, particularly with bullied children, suggests that the targets of social rejection are often those who are deemed either too aggressive or too anxious and withdrawn. Unhappily, these are exactly the kinds of behaviour often seen in abused and neglected children, or those who have experienced early episodes of isolation. What this actually means in practice is that children who have not received enough love are far more likely to suffer episodes of rejection than their peers, establishing patterns of loneliness and withdrawal that can continue well into adulthood.

It breaks my heart to think about it. But at the same time, understanding how widespread and entrenched loneliness is makes me realise that feeling any shame about it is absolutely unnecessary.

No need for shame

Over the years I spent in New York, I’d found that shame about being lonely was actually far more painful than the experience itself. Somehow, I’d become convinced that loneliness meant I had failed at life in some essential way, not just by being single, but by not being happy or satisfied in my solitary state.

But what’s wrong with failure, or feeling sad? What’s wrong with longing? I worry sometimes that we are getting too afraid of feelings, especially negative ones, even though they are an inevitable consequence of being alive. Loneliness is a human experience, a consequence of being a social animal in a complicated world. There is nothing shameful about longing for more than you have yet managed to attain, or for wanting love or closeness that you don’t have.

And once I’d dropped the shame, it was possible to see the positive aspects of loneliness. The more I realised that I wasn’t the only sufferer, the only victim, the more sensitive and tender I became – both towards myself and towards the strangers I encountered in the city. Loneliness encouraged solidarity. It made me kinder and more attuned to the invisible unhappiness concealed behind the stoicism of others. It made me more alert and more appreciative of beauty. In short, it opened up my heart – which is why, although it was among the hardest times of my life, I’m grateful for it.

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone by Olivia Laing (Canongate, £16.99) is out now