How to have a difficult conversation

It's not always easy to face difficult conversations that could bring us closer to those we love. But, as Abi Jackson discovered, it’s never too late to talk... here she shares how a difficult conversation with a parent played out, and a family therapist explains how you can approach a long-overdue discussion about past hurts...

After a flying visit home to see my parents recently, something remarkable happened. As usual, my father drove me to the train station. As usual, we trundled quietly along winding mountain roads, through familiar grassy vistas bordered by glimmering streaks of sea. As usual, there was small talk – ‘How’s work?’; ‘Fine, thank you’ – that polite precursor before someone pops on the radio.

Except this time, after a pause, my dad, John, went off-script. ‘What was it like for you growing up with Mum?’ he asked out of the blue. Just like that, he had started a conversation I had longed for my whole life.

To explain, ‘growing up with Mum’ was sometimes difficult. It was love and laughter-filled too – my kind, funny mother is one of the most generous and resilient humans I know. I love her with all my heart. But there was also a fair bit of chaos and trauma.

My mother had been addicted to heroin and developed major mental illness before I was born. She eventually managed to beat the drugs but her health was up and down. During her well phases, she was devoted and fun. She would sew my sister and I coats in fabric that matched the curtains (a rock ‘n’ roll Maria von Trapp!), teach us The Rolling Stones lyrics and take us swimming.

Childhood in crisis

However, during the unwell phases, there were long periods of psychosis and hospitalisation. Sometimes, an episode meant erratic highs, self-harm and overdoses, often losing her to endless sleep or watching her disappear into a mute, catatonic shell. Life was a rollercoaster. There were times when the first thing I would do after getting in from school was quietly check she was alive before making a start on dinner.

As long as she was well and happy, things were OK. But, when she wasn’t, we’d hold our breath and wait until things were OK again.

Deep down, I was desperate to talk about it. It was the late 1980s and into the 1990s – brushing things under the carpet was a national art. Like many families, we didn’t talk about that stuff – and the mental healthcare system was light years behind what it is today: there was no school counselling; no emotional safety nets for kids in our position.

Bubbling underneath

Instead, I learned that keeping quiet was probably best. The last thing I wanted to do was burden my dad, who already had enough on his plate. But I never really stopped wanting that conversation. Well into adulthood, those unspoken words would resurface, or play on a loop at the edges of my mind during anxious phases. I tried to keep a lid on it all but, as often happens, screw that lid too tightly and eventually it turns into a pressure cooker – tidy and contained on the outside, simmering intensely on the inside, a stew of quiet self-destruction and self-hatred – until you finally realise it’s time to heal.

For me, that started a few years ago and it’s been a gradual, bumpy process. While I made immense dents in that pressure cooker through counselling, connecting with nature and sweating it out during exercise, communicating with my family still seemed out of reach. I could never find the right words and wasn’t sure I was brave enough to even try. Now, Dad had found them for me: ‘What was it like for you growing up with Mum?’

I had no idea whether asking this question felt as monumental for him as hearing it did for me, but I swear I sensed the ‘clunk’ as a vent opened in my mind, and years of waiting were suddenly set free. The following 45 minutes in his ancient maroon Volvo, the scent of slobbery Labrador wafting around us, were some of the most meaningful and precious we had shared in a long time.

When you’ve believed for so long that you cannot have those types of conversations, that going there is just too scary, or it’s simply not worth the risk of upsetting someone or opening the floodgates, the fear can almost take on a life of its own.

The right time

In some ways, the frustration of not talking about certain things became as big an issue as the things I had wanted to talk about in the first place – because it compounded a belief that talking wasn’t an option. My job was to never make a fuss.

Now that the conversation was actually happening, I quickly realised that it wasn’t just about the things I had longed to express as a child, it was about the things I had to say now; things I wouldn’t have been able to say years earlier, before time and experience had brought greater perspective, gratitude and growth – things I wouldn’t have even known when I was younger.

I told my dad it had been tough, that I wished we had talked more and that I had grown up believing I always had to keep quiet. I also told him that, no matter what, I had always felt loved – and that I know how important that is. I told him that he had done an amazing job of holding things together and keeping our family afloat; there’s not many people who could have pulled that off. He told me he was proud of me. I told him I was proud of him.

I boarded my train to London with a glowing heart, heaving my stuffed rucksack into the carriage, alive with a new, glorious lightness in my soul.

Feeling is mutual

Before I started this article, I phoned my dad to tell him I was planning on writing about our conversation… ‘The conversation we had in the car on the way to the station,’ I said. ‘Do you remember?’ (A few months had passed.)

‘Ah yes…’ he replied. And, after a pause, he added: ‘That’s good. That felt like a real moment of connection. It was quite profound.’

My heart beamed again. It might sometimes feel as if we carry our load alone, especially on the quest for healing. Then, a window of clarity comes along and you realise that the load is universal; we all carry it, dads and daughters alike. Sometimes, we just need to change the script and connect.

So often, we tell ourselves that the moment has passed – but maybe those moments never really belonged to time in the first place. They belonged to us all along, and will always be ours to call upon, when we are ready.

Is it time for that conversation?

A family therapist’s guide to approaching a long-overdue discussion about past hurts.

Reenee Singh of the Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice (AFP) says it’s common for people to want to talk about the past, but it can be more challenging for some families, and individual therapy may be preferable. Don’t beat yourself up for leaving it until adulthood, adds Singh: ‘Silence can be protective and even help relationships sometimes. It might not have been the right time to talk when Abi was young, and it was possible for her and her father to talk later, when the issue had lost its emotional urgency. Some conversations need to take place in a reflective spirit.’

Insights that facilitate healing communication

Listening to others is as important as speaking. ‘When I work with families, it’s useful to first set a few ground rules about how you’re going to talk. This might include agreeing to take turns and not interrupt, react or cut each other off,’ says Singh.

Avoid the blame game. ‘During difficult discussions, it’s easy to blame, but that can create conflict and hamper communication. I invite people to outline their experience and how they feel,’ says Singh. This also gives a sense of responsibility over our feelings, which can be empowering and help us move on.

Being heard is powerful. Focus on the value of connecting, rather than outcomes beyond your control, such as hearing an apology. ‘A technique we use is “active listening”: People take turns to talk while others listen. Listeners then paraphrase what they’ve heard, which creates empathy. There’s value in knowing you’ve been heard.’

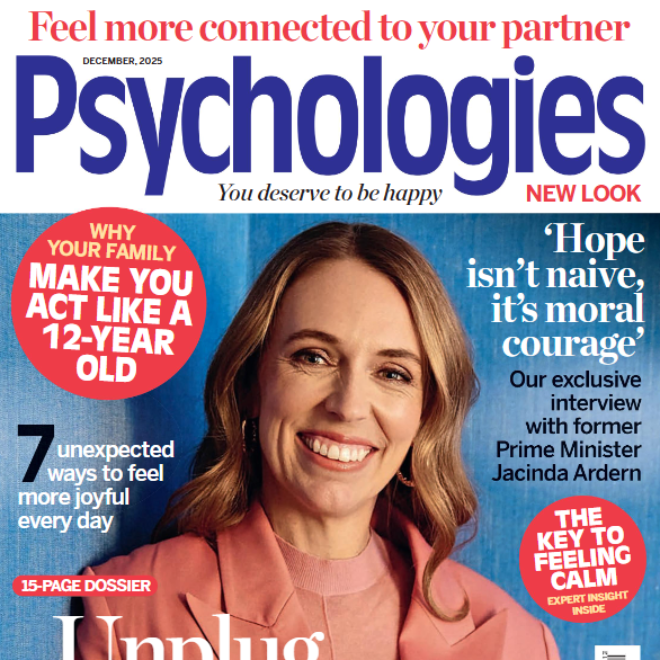

Photograph: Getty Images