5 ways to be a good neighbour

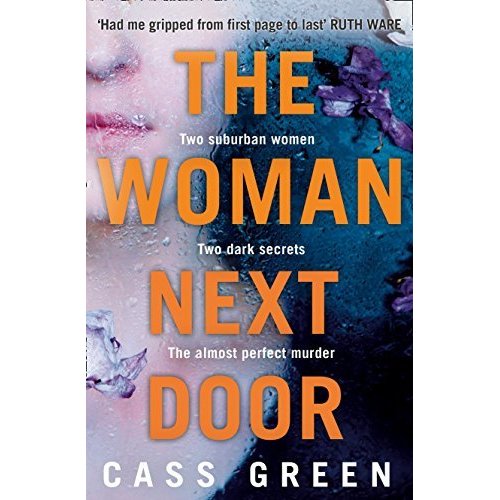

Cass Green, author of best-selling a novel The Woman Next Door, asks what we need to do to truly love thy neighbour

8 minute read

How far would you go to help your next-door neighbour? Sign for a package when they’re not in? Wheel their bins out to the main road? Help them dispose of a dead body?

This last scenario, from my psychological thriller The Woman Next Door (Killer Reads £7.99), is, of course, a bit extreme. But I wanted to explore what happens when two people with nothing in common (apart from some very dark secrets) are forced together by nature of where they live, and then embark on a crime.

People have complained about their neighbours since time immemorial. As Emily Cockayne says in her brilliant social history, Cheek by Jowl: A History of Neighbours (Vintage, £9.99): ‘As long as men have lived in shelters, they have clashed with those who live nearby.’ And after all, two of the Ten Commandments directly relate to neighbour relationships.

When everything is going smoothly, we don’t spend much energy thinking about the people next door, says Elizabeth Stokoe, Professor of Social Interaction at Loughborough University, but ‘if you are in a dispute with your neighbour then it can really badly affect your state of mind.’ She says this is because our home stops being the haven it should be. ‘If you have a noisy neighbour,’ she adds, ‘or an abusive neighbour, then coming home can be very stressful – one fears seeing them over the fence, or dreads the knock at the door.’

Most of us don’t have complete horrors as neighbours, yet we might still spend a lot of time being irritated by them. So how do we manage relationship with these intimate strangers, when the only thing in common is a patch of shared ground?

1. Look at our ‘subjective maps’

A subjective map is not the boundary between your properties. This is the one in our heads. As we grow and develop we create a representation of the world – a subjective map – according to psychotherapist Martin Weaver. ‘To understand, and be honest, about what bothers us in someone else’s behaviour,’ he says,‘we have to become aware of our own map and its various templates.

Our map is the series of beliefs and philosophies that we use to navigate the world. When dealing with conflict, Weaver says we need to consider the other person’s map, as well as our own’. He adds, ‘a question I often ask in confusing situations is “what has to be true for this person that they would think / behave like this?” This then gives me an insight into their representation of their world.’

For example, they might paint their door pink because they want to express their fun personality or perhaps they want to stand out? By seeking to understand the other person’s map, it may help take the sting out of their behaviour. It’s not about you, it’s about them.

2. Ask what the annoying décor represents to you

Once you’ve done this, you can turn the spotlight on yourself and your own map. If, for example, your neighbour’s bright pink front door winds you up, ask yourself what is really going on in your psyche. Weaver suggests the bright pink front door may represent many things: perhaps not getting your own way, being forced to accept the decision of someone else or a loss of control. He says, ‘when this is issue is realised, and owned by you, then it can be resolved.

Every time you see the pink door, you can acknowledge that you are flexible, and able to not only accept but celebrate differences in your neighbourhood.’ You may not be able to change things externally but you can change the way you think about them. The pink door becomes a symbol of how you are in control of your thoughts and your inner world, which makes you feel secure and good about yourself every time you drive home.

3. Have a word with your shadow side

‘Most of us spend all our time in fear of our shadow side,’ says Weaver. Our shadow side is the part of ourselves that we judge to be inferior or unacceptable and deny in ourselves and often project onto others. It’s likely that the answers to minor irritations are that we see in others the very shadow side we fear to express in our own lives.

Our contempt for the pink door may be that a part of ourselves really likes it but our shadow side thinks it’s too loud or trying to stand out. This opens up all sorts of fears about our own standing in the family, the street, the workplace and the community.’ So if some small, niggly thing is irritating and you’re not prepared to say anything, maybe it’s time to have a dig around the shadows and have an honest look at what we are really rejecting in ourselves.

Ask yourself – what judgment are you making against your neighbour? Eg: ‘they are just trying to show off and stand out.’ Then ask yourself what could you admire about the owner of the pink door? Eg: ‘she’s not afraid of being judged or to express herself.’ Ask yourself how you can express yourself more authentically in life? Now every time you drive up to the pink door, you can see it as an invitation to bravely express yourself authentically in your life and again feel good and inspired every time you drive up to your house.

4. Find your ‘friendly distance’

In my book, lonely, odd Hester wants to be a part of yummy mummy Melissa’s life. Unfortunately, the feeling is not reciprocated. As she obsessively tracks the contents of Melissa’s Ocado delivery she says, ‘I’m not snooping. It’s just the only way I can keep in touch with what’s going on in her life.’

Although this is extreme, an expectation gap isn’t that uncommon according to Lynda Cheshire, a sociology professor at the University of Queensland who carried out a major survey on neighbours. She says, ‘there is an important difference between friendliness – a positive disposition towards another which may only require limited engagement – and friendship. This distinction may not always be well-understood or agreed upon between neighbours.’ Ask yourself some tough questions about whether there is a balance to some of your neighbour relationships – either way round.

So how do you manage to stay friendly without becoming best friends? Elizabeth Stokoe has a good tip. ‘Initiate talk with a friendly, “how are you doing?”’ she says, ‘but do it while walking or on the move. This signals that you’re not stopping for a chat, and it’s very hard conversationally not to respond to a hello!’

5. Learn to say no

Weaver believes an understanding of the internal map mentioned above will, ‘give us the permission we need to choose what we’ll accept. I think that often we know where the land lies but lack the confidence to say so, or to say no to our neighbours’. So if you don’t want to go to barbecues every week, or join the street book club, don’t allow yourself to be reeled in, where you will only feel resentment. Just say no to begin with.

While we can’t choose who we end up living next door to, most of the time, we manage to rub along fairly harmoniously. Linda Cheshire says, ‘our research shows that most neighbour nuisances are low level problems that are mere annoyances, managed by talking to the neighbour or doing nothing and are recognised by people as an everyday fact of living among others.’

She concludes, ‘this would suggest that most of us are pretty good neighbours and adhere to these unwritten rules of neighbourliness.’

So, having once lived in a flat that had noisy neighbours below, through both party walls and across the street, I’m very blessed with my current ones. If they ever start messing up the bins, I’m going to smile and shrug. After all, it’s hardly murder, is it?

Photograph: iStock